Beth Jackson

CURATING FEMINISM CONFERENCE

Sydney College of the Arts, 23-26 October 2014

Panel 3 – curating regionalism

Saturday 25 October 2:30-3:45pm

Glenda Orr: Bimblebox Sky Map 1, (detail) 2013. Bimblebox sap on blind embossed rag paper. Photograph: Carl Warner

Thank you for the invitation to be here and for having me – to CAF – Jacqueline Millner, Jo Holder & Catriona Moore and Mikheala Rodwell.

I’ve been asked to reflect on a regional touring exhibition I’ve curated entitled Bimblebox: art – science – nature which is currently showing at Bunbury Regional Gallery in Western Australia and will be touring nationally for the next 2 years. I’m grateful for the opportunity to reflect on the exhibition in this context.

In the ‘Prolegomenon’ to her work Revolution in Poetic Language 1974, Julia Kristeva writes,

our philosophies of language, embodiments of the Idea, are nothing more than thoughts of archivists, archaeologists, and necrophiliacs…. These static thoughts, products of a leisurely cogitation removed from historical turmoil, persist in seeking the truth of language by formalizing utterances that hang in midair, and the truth of the subject by listening to the narrative of a sleeping body…. And yet, this thinking points to a truth, namely, that the kind of activity encouraged and privileged by (capitalist) society represses the process pervading the body and the subject, and that we must therefore break out of our interpersonal and intersocial experience if we are to gain access to what is repressed in the social mechanism: the generating of signifiance [p.27]

The discourses of power treat the subject as a cadaver, killing and preserving its object before setting to examine it scientifically. It’s beyond irony that this 2nd Age of Extinction will be so meticulously documented. These are 15 black-throated finches from the Queensland Museum – a photographic artwork by Emma Lindsay, referencing the official siting by Birds Australia of a small flock of 15 blackthroated finches at Bimblebox Nature Refuge in 2011. The black-throated finch is the only officially endangered species to be officially sited at Bimblebox. (Refer to pdf at bottom of page for this artwork).

In the museum we are compelled to be fascinated by the remains of a process while turned away from the dynamic nature of the process itself.

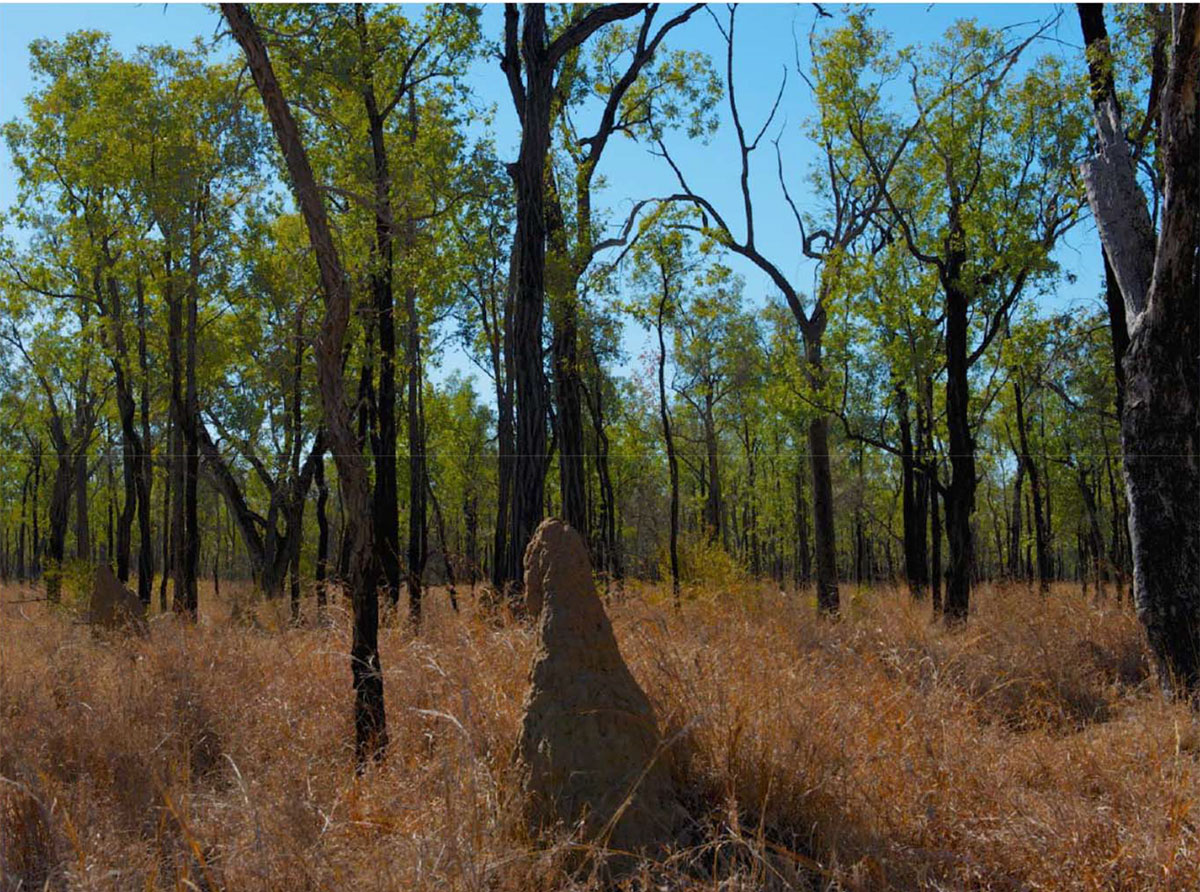

Ironbark forest, Bimblebox, 2013, digital photograph by Tangible Media

This is the Bimblebox Nature Refuge – 8000 hectares of Desert Uplands country in Central Queensland. Formerly Glenn Innes Station, the property was used for cattle grazing but was never cleared. This is original country. Mostly open eucalypt forest – this is a stand of iron bark trees (you wouldn’t think them hundreds of years old), lots of termite mounds, lots of grasses including spinifex. The Desert Uplands is located where the eastern wetter country meets the dry inland. It’s a biodiversity hotspot. In many ways quintessential Australian bush with its slow reveal. The property was purchased by a group of individuals in 2000 to save it from land clearing. A federal government grant assisted with the purchase and a state government Agreement officially recognises it as a Nature Refuge and incorporates it within our National Reserve system of protected areas.

Kristeva writes: the capitalist mode of production produces and marginalizes, but simultaneously exploits for its own regeneration, one of the most spectacular shatterings of discourse [p.29]

Capitalism places a demand on all signifying practices – to mediate material exchanges, to perform equations or equivalences of value. It’s a terrible burden that can be felt within our speech. Kristeva imagines a new language — or a new orientation to language — that does not fragment and compartmentalise the different possibilities of language.

Dusky Woodswallow on the fenceline, Bimblebox, 2013, digital photograph by Beth Jackson

Perhaps it is from this newly oriented position described by Kristeva that an environmental enunciation can be made – that Bimblebox is ‘theirs’ not ‘ours’ – it belongs to the flora and fauna, geology and micro-climate from which we are separate and to which we are so deeply connected.

Can this relationship be felt within our speech? Is it possible to hear ‘theirs’ within ‘ours’ within our own speech? This question was the basis of my curatorial rationale for this exhibition which I entitled ‘from under the breath’.

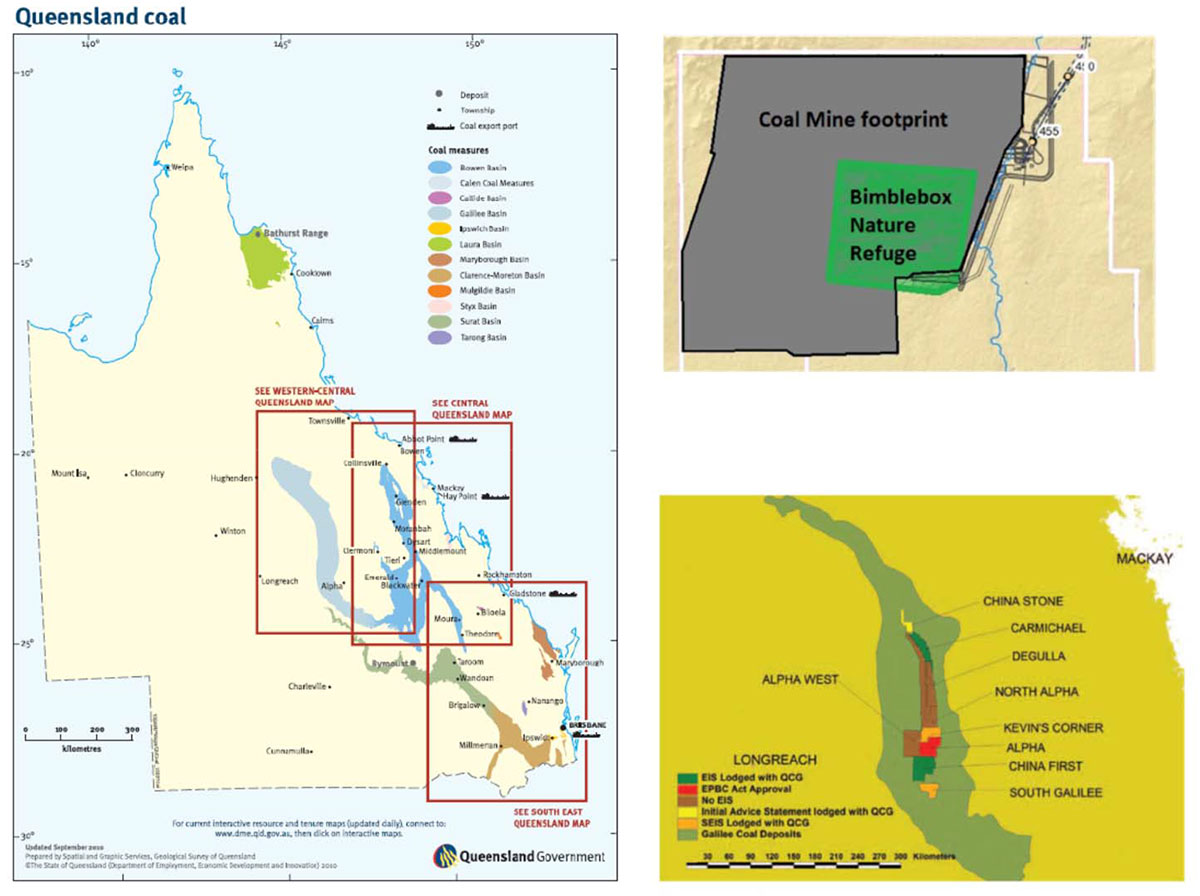

1. ‘Queensland Coal’, prepared by Geological Survey of Qld, © The State of Qld 2010; 2. Waratah Coal’s China First Mine Footprint, E3 Consulting, 2011; 3.Proposed Galiliee coal mines and their status, ‘Draining the Lifeblood’ Report, 2013.

Bimblebox is threatened with destruction from coal mining. Mining claims have right of way over Nature Refuges. The proposed China First mine owned by Clive Palmer’s company Waratah Coal has state and federal government approvals to open cut half of Bimblebox and long wall the remainder.

This is the mine footprint. Bimblebox is located about 50km north-west of Alpha in Queensland’s Galilee Basin. The China First mine is one of nine mega mines proposed for the Galilee – any one of which is many times larger than our largest Australian mines. These will be some of the biggest mines in the world.

The spectacular shattering of discourse produced by capitalism, Kristeva writes, ‘explodes the subject and its ideological limits’. Just like these mines will explode the landscape – this violence, these acts of eco-cide, will take our landscape beyond recognition and repair.

The photographic archives of the Mercer Studio local to this region, uncovered by artist Fiona MacDonald, have been reproduced and overlaid with a photograph and schematic of the Alpha Mine test pit. This test pit is the only coal so far to be extracted from the Galilee Basin. The Alpha Mine originally owned by Gina Reinhart, is mostly now owned by her Indian investors GVK. (Refer to pdf at bottom of page for this artwork).

These works evoke the layers of colonial history and white settlement over the landscape and our deep dependence on coal.

Alison Clouston & Boyd’s work Coalface is monstrous, an expression of horror as we approach the tipping point of dangerous climate change. The work is a multimedia installation within the touring exhibition but can also be worn for performance and protest. This is an image of Alison outside the law courts in Sydney protesting a NSW coal mine operation.

Coal in the Galilee is thermal coal for electricity generation. Coal extraction and burning is by far the most potent contributor to CO2 emissions that drive global warming.

Returning to Kristeva, the explosion of the subject by capitalism has a triple effect and the first of these is the alteration in the status of the subject – her relation to the body, to others and to objects.

The economy, as we so politely call it, is an all pervasive overlay on all our social and political discourse effecting, as Kristeva says, our status, our relations to our body, to others and to objects. (Refer to pdf at bottom of page for this artwork).

Artist Camp, Bimblebox, 2013, digital photograph by Tangible Media

The Bimblebox Art Project, from which this exhibition springs, was instigated by artist Jill Sampson who has organised a series of artist camps on the Nature Refuge, hosted by its caretaker Ian Hoch and part-owner Paola Cassoni.

This is the campsite, under the beautiful yellow jacket trees.

(L) Paola Cassoni, Ian Hoch, Jill Sampson, artist camp, Bimblebox, 2013, digital photograph by Tangible Media. (R) Ian Hoch on horseback, Bimblebox, 2014, digital photograph by Beth Jackson

This is Paola Cassoni on the left sitting down with Jill Sampson and Ian Hoch standing beside her.

Bimblebox is still a cattle property. It is grazed in low numbers to provide income support and has been studied by CSIRO and others in relation to sustainable farming practices and biodiversity protection. It is remarkable to see nature preservation and food production hand in hand.

Grid of ‘artists at work’, digital photographs by Jill Sampson, left to right, top to bottom: Mick Pospischil 2013; vegetable dyes from native grasses, Jill Sampson; tree rubbing, Jude Roberts; Donna Davis with plant specimens; Alison Clouston, construction with birds nest; Gerald Soworka with drawings; Howard Butler with coolamon.

Late capitalism’s modes of production are now so integrated with science and technology that, Kristeva states, they go beyond normative discourse (linguistics and ideology) and interface directly with process. This results in the second shattering effect of the subject which is the display of its formation – our inherent instability, our self as work in process, our schizophrenia.

These are the artists working at the camps. Environmental art is fundamentally about process – a material and corporeal practice of signification seeking to indicate and describe its own position.

The frottage that Jude Roberts is creating from the dead trees that take hundreds of years to form and provide vital habitat for hollow nesting birds and other creatures, features within the touring exhibition. Jill Sampson has incorporated these woven grass forms into a larger installation for the exhibition. (Refer to pdf at bottom of page for these artworks).

Jude Roberts‘ other work included in the exhibition, Shroud for an ancient basin, maps the phenomenon of water interacting with a paper tarp and crushed charcoal – spilling and btrickling, soaking and staining.

Bimblebox like most of the Galilee (coal) Basin is located in a recharge zone for the Great Artesian (water) Basin – the largest reserve of underground fresh water in the world. There is no permanent water on Bimblebox – the property and the surrounding region including the towns of Alpha and Jericho are completely reliant on bore water. Mining, through its use of huge volumes of water and through the mining activity itself poses an enormous threat to water resources.

In this recharge zone, rainfall seeps into the basin through a series of shallow sandstone aquifers. The water takes thousands of years to leech down and travel across Queensland to feed springs in north-western New South Wales. It’s the chain of sandstone aquifers that are most threatened by mining.

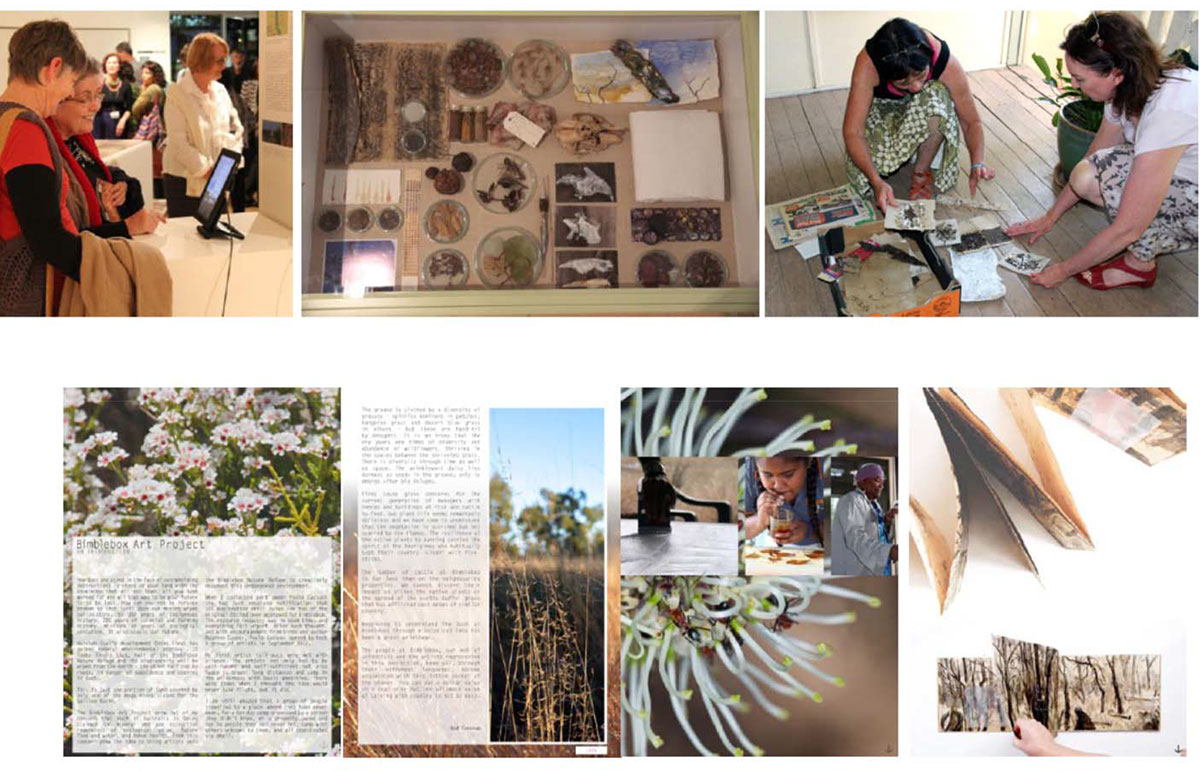

Exhibition images: Opening night, Redland Art Gallery, photograph courtesy Redland Art Gallery, 2014; Curiosity Cabinet, photograph by Jill Sampson, 2014; Liz Mahood and Beth Jackson in conversation, photograph by Jill Sampson, 2013.

The third effect of the shattered subject identified by Kristeva is the emergence of ‘fragmentary phenomena’ which underscore the limits of socially useful discourse – attesting to what is repressed, namely the process that exceeds the subject and her communicative structures. Art is one of these phenomena and here Kristeva asks under what conditions does art displace the boundaries of socially established signifying practices leading to socioeconomic change and even ultimately to revolution, or under what conditions does it remain a blind alley, a harmless bonus offered by a social order that uses this esoterism to expand, become flexible and thrive? [p.30].

Perhaps, when it comes to the fragmentary phenomenon of contemporary art, these questions are curatorial ones. This exhibition project involved an intensive interdisciplinary and social effort. There is a vital online and ongoing component to the project in the form of an artist-run blog. There were visits to most of the artists in their studios where Jill and I recorded interviews. There are essays from scientists and a body of nature photography and film. This material has been published in a digital catalogue available as a free app for the iPad. An iPad tours with the show as well as a cabinet of materials collected from Bimblebox and donated by the artists.

We are determined to use the gallery as a social space, an inclusive social space, different to the polarising politics of the media spectacle. We want local communities to engage, to have their own conversations about the impacts of mining and the futures of food and water security, environmental health, biodiversity and our beautiful, precious, fragile landscape. We want mart to be a catalyst for social change – that reorientation that Kristeva yearned for and we so desperately need.

Of course Kristeva’s elaboration of the subject as evolving, desiring, as a constant work-in-process, as a living thing and not a cadaver, involves the deconstruction of and challenge to her own field of psychoanalysis which has its own necrophilic tendencies. So too, as a curator, it is essential to relate to art as a process and a series of processes – art as idea, as material phenomena, as force and form, as well as presented object – and to understand the curatorial relationship within those processes. Like the museum, the gallery often seeks to fetishise the remainder of the process and allow curator’s to wear cloaks of invisibility.

This is I think to deny the real value of art, that is, its intimate connection to life and to the subjective chora – that charged field that orders our drives, generating an arrangement of desire and subject formation that is before the separation of aesthetics and ethics. We’re unstable – in desperate need of kindness and care, a sense of belonging, love, intimacy, health and wellbeing – social and environmental sustainability.

The truth of this project is that Bimblebox and its owners have given artists as much if not more than they have given it. And this reciprocity is living and ongoing.

Grazier and caretaker and passionate environmentalist Ian Hoch provided an essay for the digital catalogue and his words describe this corporeal gift:

The smell, back then and still now. At times, that distinctive but indescribable amalgam of many. The sexy sweet scent of ovulating spinifex, a raw emanation from moist red earth, the wavering fragrance of wattle blossom surfing the breeze, an overpowering smack of yellow wood carried a crooked mile from source. Together, on a certain damp day, blended in intoxicating cocktails of molecules, transferring to body, traversing blood/brain barrier and serving to elevate mood, enhance cognition and soften the hardest of hearts. Odours, like the diminishing dawn chorus, now sadly and conspicuously absent from our towns and countryside. Gifts from Bimblebox to the world.

Reference:

Julia Kristeva, Revolution in Poetic Language: Prolegomenon, 1974 as reprinted in The Portable Kristeva, Kelly Oliver Editor, New York: Columbia University Press, 1997 [pp.27-31]

Download full pdf of this presentation here

All images reproduced with kind permission of the artists and photographers.